Jobs To Be Done (JTBD) is a framework that helps you understand why and how people buy products.

Understanding your customers’ JTBD dramatically increases the likelihood of connecting your product with the right buyer at the right time.

What does Jobs To Be Done help you identify?

JTBD can help you identify why customers buy certain products or experiences. The JTBD premise is that people don’t buy products—they hire them to do a job. The “job” is a need that your customers are trying to fulfill.

When you know why people hire or fire your product, you can better understand what drives them to buy. You can also predict their behavior because the problem they are trying to solve shares the same eight elements of every JTBD. Essentially, they want to make the same progress in the same context of their lives. It’s about the crux of what they’re trying to do.

Jobs To Be Done Steps: Uncovering Your Customer’s JTBD

Let’s take a closer look at the eight elements of a JTBD through a simple story.

What “job” causes someone to hire a milkshake at eight o’clock in the morning? That’s what we asked ourselves while investigating an anomaly occurring at multiple restaurants within a chain before smoothies for breakfast were a thing.

The restaurants weren’t supposed to sell milkshakes at breakfast, but several did—and rather successfully. So, we set out to understand what “job” people were hiring milkshakes to do for breakfast.

First, we drove to a store where this anomaly occurred and just sat and watched. Immediately, we noticed some similarities between these consumers. They arrived alone before 8:00 a.m., bought only a milkshake, and immediately returned to their cars and drove away.

“That’s curious,” we thought.

So, the next day we sat in the parking lot and approached these people as they left the store post-purchase.

“Why did you buy that milkshake?” we asked. “What would you normally do for breakfast?”

We wanted to understand why they bought that milkshake that day, at that moment. After interviewing numerous customers, we unpacked all the conversations, looking for a common thread. Not everyone had the same reason, but we found one cluster of customers in the same circumstance, fulfilling the same “job.”

As it turns out, each of these consumers had a long, boring commute to work. So they needed something to help pass the time that would keep them full until lunch. And since they were driving, it needed to be something they could handle with one hand on the wheel.

The milkshake did this “job” quite well.

It took at least twenty minutes to suck the thick liquid through the straw, which kept them busy—a nice respite from the long, boring commute. It was self-contained and created no crumbly mess. When they finally got to work, they tossed the cup in the trash. As far as navigating the road, the milkshake was ideal. It can be handled easily with one hand on the wheel and fits nicely in the cup holder. Finally, the people we talked to told us that when they hired the milkshake, they stayed full all morning, which made them more productive and pleasant to be around.

Let’s break down the “job” of the 8:00 a.m. milkshake into the core eight elements:

- Context

- Struggling Moments

- Pushes & Pulls

- Anxieties and Habits

- Desired Outcomes

- Hiring and Firing Criteria

- Key Trade-offs

- Basic Quality of the JTBD

1. Context

This element is about what’s going on in a person’s life. It’s a broad, big-picture view. For example, each person we spoke to talked about their long, boring commute to work.

2. Struggling Moments

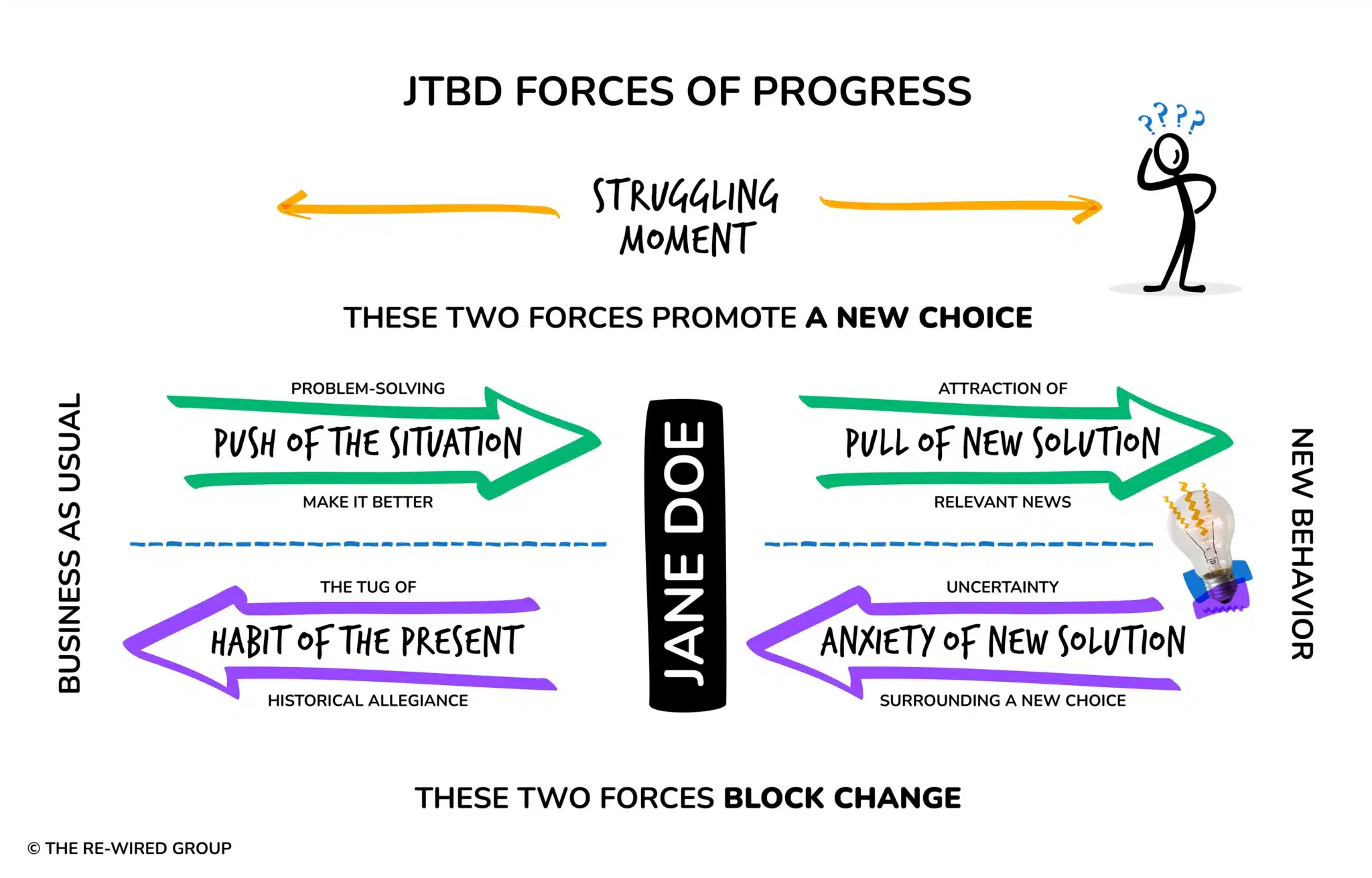

A struggling moment is a point in time when you realize that something can be better. It’s the emotion that’s driving the change. If you can show consumers a better way, better people will want it. For the person hiring the milkshake, it’s about solving the hunger now, so they are not hungry later.

Finding where people are looking to make progress is what innovation is all about. These struggling moments are the seed for all innovation. You have to find that struggle—the moment where there’s a push toward the future and a pull from the past. The point where what they’re doing now isn’t working, and the outcome they want is better than what they have now.

3. Pushes and Pulls

The pushes are about the circumstance that causes the struggling moment. Here, the push is boredom while driving and the energy needed to make it through the morning. The pulls are based on the struggling moment and help you define what progress looks like. Here, the pull is the notion that drinking the milkshake will pass the time and fill your stomach.

4. Anxieties and Habits

The anxieties are the concerns a customer has about the new future. The person worries, Will it fill me up? Is it going to give me a sugar rush and a subsequent crash? The habit is about the old thing they must give up. So, here the person thinks, But I really like my Egg McMuffin.

5. Desired Outcomes

This element is about what you wish or dream for the world to be when you change to the new—it’s an accumulation of the pulls. What does satisfaction look like? It’s about getting to work and being productive.

6. Hiring and Firing Criteria

What things must be there for the customer to hire something? What are the criteria for hiring to solve that problem or that job? Here, the hiring criteria would include the drink’s thickness: Does it take long enough to drink to help me pass the time? The firing criteria are the things that will cause my product to get fired. These consumers didn’t want to feel like they were eating dessert for breakfast, so making the drink too sweet would be a firing criterion.

7. Key Trade-offs

This element is about what the person is willing to give up to achieve their goal. Here, they are eager to give up their preferred breakfast for a solution that will fill the time and ease the boredom.

8. Basic Quality of the JTBD

Each “job” has its essential quality or things it must do. Most people think about basic quality from a product standpoint. That’s important, but each “job” has its basic qualities too, certain things that you can’t violate. Here, the milkshake must last long enough to pass the time.

As innovation consultants, we were responsible for taking these requirements over to the supply side and figuring out what they meant. Should we make the straw smaller or the milkshake denser so it would take longer to drink? Did it need to be less sweet or more filling? The customer can’t tell you the answer. It’s your responsibility to figure out the offering or series of offerings that fit the gamut of their needs through other testing. Finding the cluster told us where to dig, but we still needed to do more work and testing.

When you understand the “job” your consumer needs done, reformulating your product from the business side—the supply side—becomes easier. For example, it’s easier to see that you must reformulate the milkshake offered at breakfast into more of a morning menu item. It needs to be thick enough to take twenty minutes to drink and not too sweet, so people don’t feel like they’re having dessert for breakfast.

Additionally, you will realize that your competitive sets are not just other milkshakes but any other food that fulfills the “job”: self-contained, long-lasting, one-handed, and filling.

What’s an Actionable JTBD?

An actionable JTBD is clear when it’s in consumer language and abstracted at the right level.

Here are poor examples of abstraction:

- If you go too high, you make a product that’s too broad. You think everyone will say yes, and everybody will want it. You think it’s the golden thing that will make you $15 billion.

- If you go too low, it only applies to two or three people.

You need to find the jagged place in the middle that allows you to have three to five clear JTBDs. It should be broad enough that it will enable you to group large segments of people with similar but not identical circumstances but tight enough that you cannot fit people from different circumstances into the same “job.”

You do not want 100 “jobs” for a product or service, nor just one. You’re looking for three to five JTBDs.

When you have clear JTBDs, you can do two things:

- Look at each of the eight elements and define them meaningfully.

- Look at people and say, “I’d put them here because of that, or I’d put them there because of this.”

The key is that a JTBD should be guided by the consumer’s intent and actions, not by common language and aspirations.

If a JTBD depends on the economy or technology, that’s not a “job.” A “job” is independent of those things. The JTBD is about the person and what they want to accomplish.

Think about traveling musicians from the Middle Ages, a transistor radio, and an iPod. What do they all have in common? They’re all things that allow someone to bring music wherever they go instead of having to follow the music. The technology advanced over time, but the core, causal “job” stayed constant. Technology didn’t create the “job.” The demand was already there. Technology enabled us to get the same “job” done better, faster, cheaper, and more conveniently, but it did not cause the struggle that created the demand.

At its core, a JTBD must help people make progress.

What is NOT an Actionable JTBD?

Let’s explore some common misconceptions:

A JTBD is not a demographic.

People act based on their situations and what they want to get done. Age, gender, and income are not the deciders. What demographics tell you is often misleading. You would never see a twenty-year-old driving a BMW if demographics were good predictors. Demographics would tell you that your product needs to reach a consumer at a certain age and income level.

A JTBD is not a persona.

People often ask me, “Well, aren’t ‘jobs’ just personas?” No. Personas help identify a group of people who will typically act a certain way. Conversely, “jobs,” tell you how the person acts in a specific context. Personas are a supply-side look at the world without the trade-offs, context, or outcomes from the eight elements of a JTBD.

For example, food companies often describe their buyers by saying, “They’re clean eaters. They want organic. They want a clean label.” But then you go into the consumer’s house and find a chocolate bar and a tub of ice cream: “How did that get there?”

Inevitably, the person will slump their shoulders and say, “Well, you know those times when you just have a terrible day,” or, “I eat that other stuff so that I can still fit into my clothes while eating ice cream.” That’s a JTBD—the moment where they’re struggling with something and make a trade-off.

A JTBD cannot belong to a company.

Only people have JTBDs, not organizations. Organizations have mission statements, strategies, etc. But even when selling B2B, you must find the JTBD of the person hiring you to make the change for the organization. That person is willing to use their personal capital to make the purchase happen.

A JTBD is not person-specific.

People can be hired for different “jobs” at different times, even throughout the same day. For example, I may have one set of circumstances and outcomes that drive me to buy a milkshake at 8:00 a.m. and a different set in the afternoon. In the morning, I want a milkshake that’s not too sweet so that I don’t feel like I am having dessert for breakfast. I’m buying it as a treat in the afternoon, so I want the sweetness. I’m the same person, but my circumstances and the outcomes I seek are different.

“Jobs” are not people-specific. They’re moment-in-time specific. When determining a person’s JTBD, you must be specific about the person in a particular circumstance. What are they trying to get done? What forces are they acting upon?

There are no impulse buys. Everything is a JTBD.

An impulse buy is a learned behavior that allows someone to go through the decision-making process very quickly. For instance, every time you go to the refrigerator, you’re going through a decision-making process. Because you have done it a million times, you move through the decision quickly.

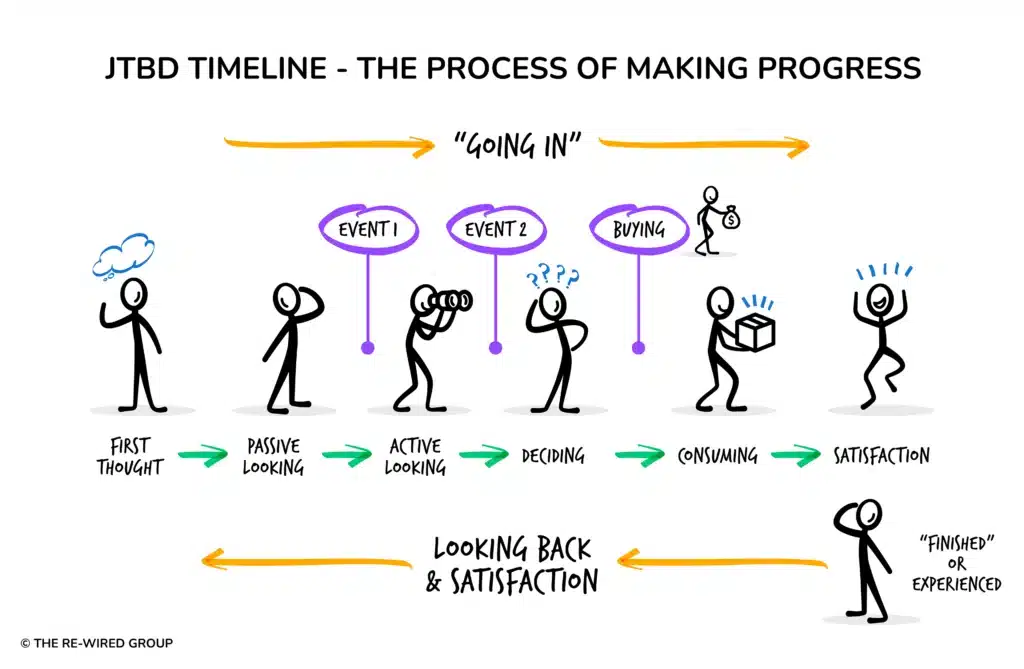

How to identify Jobs To Be Done

The best way to understand Jobs To Be Done is to talk to people who have already decided and are using your product or service. When you speak to them after they have chosen—good or bad—you can unpack their context, the trade-offs they were willing to make, and their overall satisfaction.

- What were the key drivers of satisfaction?

- What were the key drivers of hiring and firing a product or service?

Most people think you must talk to a bazillion people to capture demand. We’ve found that if you use robust design experiment principles and pick interviewees from varied backgrounds, you can do as little as ten. If you’re new at interviews, consider fifteen or twenty but not 100. It’s not science. You’re not trying to get statistically significant results.

There are two interview strategies we employ at Re-Wired to help separate ourselves from supply-side thinking:

- Unpack vague language.

- Don’t interview alone.

Unpack Vague Language

This approach goes back to the notion that people have many different definitions for the same words, so you must unpack their meanings. Unpacking language is about getting to the causal mechanism of what a consumer means by a word.

So, for example, if someone says, “I want to be healthy,” we respond, “We have our definition of ‘healthy,’ but we need to understand your definition of ‘healthy.’”

“I want to feel good,” they might say.

“Why do you want to feel good?” we’ll ask.

I want to understand them at a much deeper level: Why don’t they feel good? What are the circumstances for them not feeling good? And how do they measure feeling good or healthy? Only then will we understand their meaning of “healthy.”

On the supply side, people often look for their consumers’ words and collaborate and build around them. But you need a deep understanding of the consumer’s meaning, not just the terms used.

Don’t Interview Alone

You must continually check yourself to prevent inserting your own biases into the interview process. At Re-Wired, we check ourselves by having multiple people in the room when conducting consumer interviews. When more people are in the room, the variety of views becomes evident, and asking the questions becomes natural. Even after the interviews conclude, we debate each other on our understanding of the consumer’s meaning. We are constantly challenging ourselves to disengage our minds from our current knowledge.

Real examples of how companies capture value with JTBD

Software Development: Hudl

Hudl’s platform, initially focused on supporting football, would help players and coaches to learn from games, save time and ultimately “win”.

But as they grew, so did the level of complexity in helping support its customer base. Inefficiencies occurred in the sales process, and features were never used by paying customers.

They partnered with The Re-Wired Group to help understand the ‘why’ behind their customer actions. By doing so, they were able to increase the success of product launches in new markets by developing features that mattered.

Software Development: Basecamp

Basecamp struggled to understand why companies that were not software developers wanted Basecamp. They didn’t know which features were important to these new customers or how to define themselves now that people were using it differently from its original premise.

Basecamp and The Re-Wired Group uncovered five customer jobs that changed how Basecamp thinks about its entire business. They created new marketing messaging, positioning, sales demos, and features around these new jobs, which led to incredible user and revenue growth. As a result of this consumer behavior consulting and insight, Basecamp now has hundreds of millions of users and continues to grow yearly.

Product Management: Intercom

After three years, Intercom’s growth had stalled. Their customers weren’t using their entire product offering, and they didn’t know why. They wanted to see if they were building the right products and if people were hiring them for additional jobs they weren’t aware of.

We conducted JTBD interviews to identify four core jobs people hired Intercom to do. Intercom redesigned its product and changed its go-to-market and communications strategy for these jobs. Once they did, through this new focus on cross-functional alignment between teams, they tripled their revenue and grew their company by 500% in 18 months.

Accounting Software: Autobooks

Autobooks was struggling with their sales demo. Together, we dug deeper into their struggle and realized that one of the biggest problems with their demo was that it wasn’t effectively meeting its clients’ hiring and firing criteria.

To address this issue, Autobooks created three separate sales demos for prospects at different stages in their customer journey. Additionally, each Autobooks customer job has a distinct timeline so they can see where each prospect is in their decision-making process and what they can do to support them. These changes have helped them close twice as many leads in half the time.

Understanding Jobs to Be Done

A JTBD is pure. It’s a pristine view of demand independent of supply. When identified effectively, it helps predict future buyer behavior. But the JTBD is not the whole picture of how to design a product. A JTBD is separate from supply, but ultimately when you design a product, you must weigh the needs of the supply side.

A “job” is about looking beyond the decision to the reason why someone made the decision that they did. Often, consumer behavior will seem irrational, but that’s because you haven’t truly uncovered the eight elements of a JTBD. The irrational becomes rational with context. At the core, people just want to make progress in their lives.

So, how do you know if you’ve uncovered your customer’s JTBD? Ask yourself the following questions:

- Do I know the consumer’s competitive sets for my product?

- Do I know what the consumer has hired and fired in the past and why?

- What makes my offering different?

- What struggle is the consumer trying to solve?

- What is holding them back from consumption?

- What is pushing or pulling them to the new idea/product?

FAQ

Bob Moesta, the president and CEO of The Re-Wired Group, helped develop the JTBD framework alongside Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen. Since creating the theory in the mid-nineties, Bob has continued developing, advancing, and applying the innovation framework to everyday business challenges.

JTBD research often consists of Jobs interviews. Listening to people who have recently made a change—not about what they bought, but rather why they bought—can help you identify the intersection of the hiring criteria and demand frameworks. When you understand the forces acting on a consumer when they make a choice, you can understand the mechanisms of value beyond the product. You can also see what would help them make more progress than what they are choosing today.

JTBD is a theory of innovation and customer behavior. It enables innovators to be more creative on the technological side, offering solutions to help consumers accomplish jobs in new ways that are much better than current options instead of developing product features from a very ambiguous perspective.

JTBD stands for Jobs To Be Done.